South Korea and the United States long have worked together under a nuclear energy cooperation deal that limits certain fuel-cycle activities. Under this agreement, South Korea cannot reprocess spent nuclear fuel or enrich uranium above certain levels without explicit U.S. permission. These restrictions aim to prevent any misuse of nuclear materials and to uphold non-proliferation norms.South Korea runs dozens of nuclear power plants and relies on imported fuel.

What Changed: U.S. and South Korea Agree to Talk About Reprocessing

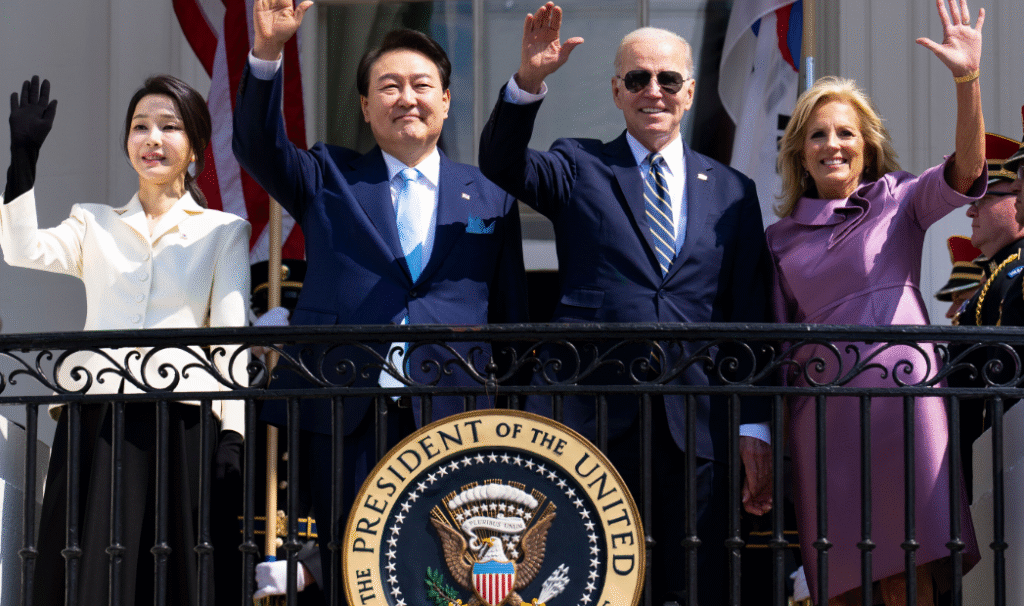

In a recent summit between President Lee Jae Myung of South Korea and U.S. President Donald Trump, both countries agreed to begin discussions about revising the agreement to allow South Korea more freedom for fuel reprocessing. Foreign Minister Cho Hyun announced publicly that Seoul wants to be able to reprocess spent nuclear fuel and make nuclear fuel itself, under industrial and environmental justifications—not for building weapons.

The decision to revise does not mean immediate changes; rather, it signals a mutual willingness to engage in dialogue. In other words, both sides consent to negotiate. At the same time, South Korea emphasized that any revision must strictly adhere to non-proliferation rules. Moreover, it assured the international community that there is no intention to pursue nuclear weapons.

Why Revision Gained Broad Support in South Korea

Several pressures built momentum for change in South Korea. First, the country expects its storage for spent nuclear fuel to reach capacity in coming years. Without more avenues to deal with used fuel, environmental and safety concerns grow.

Second, the shift responds to local demands: nuclear power plays a key part in Korea’s energy mix and industrial strategy. Leaders in Seoul view more control over the nuclear fuel cycle as enhancing energy security, helping with waste management, and cementing South Korea’s technological leadership in nuclear engineering.

Third, South Korea’s growing diplomatic and strategic concerns particularly amid rising instability in East Asia—further underscore the need to reduce dependency on foreign nuclear fuel supply chains. By strengthening domestic capabilities, the country not only gains greater autonomy but also mitigates risks associated with external disruptions.

U.S. Perspective and Assurances

From Washington’s side, the U.S. appears open to discussions but makes clear that anything more permissive must come with strong safeguards. U.S. officials emphasize that any revision must strictly adhere to nuclear non-proliferation norms. They also want transparency, verification, and sufficient legal guarantees that any reprocessing or enrichment remains for peaceful, civilian uses.

The U.S. also has to consider its exports, international obligations, and its own legal frameworks. Changes will likely need approval through legislative or executive processes, perhaps even oversight by Congress, depending on the scale of changes proposed.

Challenges Rises on Technical, Political, and Diplomatic

Even though consensus has emerged to discuss revisions, moving to actual change involves challenges. On the technical front, reprocessing and enrichment require complex infrastructure, trained personnel, safety protocols, and environmental protections. These are expensive, require careful regulation, and often draw public concern.

Politically, there are domestic voices both for and against deeper nuclear fuel autonomy. Opposition parties, civil society, and non-proliferation experts warn that loosening restrictions could send the wrong message in the region and raise tensions with neighbors.

Diplomatically, South Korea must manage not just the U.S. relationship but also regional concerns (especially from countries like Japan) and global bodies overseeing nuclear safety and proliferation. Any change must avoid undermining trust with allies or violating international treaties.

US Removes India Map from Trade Release After Pakistan Protest

US Removes India Map from Trade Release After Pakistan Protest  South Korea’s Foreign Exchange Reserves Hover at Low 20% of GDP Amid Vulnerability Concerns

South Korea’s Foreign Exchange Reserves Hover at Low 20% of GDP Amid Vulnerability Concerns  South Korea’s 1.9% growth trails US again

South Korea’s 1.9% growth trails US again  US Ambassador Nominee’s Iceland State Joke Sparks Backlash

US Ambassador Nominee’s Iceland State Joke Sparks Backlash  Korea’s M2-to-GDP ratio twice US., controversy renewed

Korea’s M2-to-GDP ratio twice US., controversy renewed  Iran Warns “We Are Ready for War” as Crackdown on Protests Intensifies

Iran Warns “We Are Ready for War” as Crackdown on Protests Intensifies