Pakistan made steady progress in reducing poverty. The early 2000s saw millions move out of deprivation, largely due to rising employment in construction, trade, transport, and other urban services. By 2018–19, the share of Pakistan’s population living below the national poverty line had fallen close to 22 percent, compared to over 60 percent in 2001–02. This achievement stood as evidence that consistent growth and urban migration could lift lives. Yet the latest World Bank report reveals that these gains have now been undone, with poverty levels climbing back to more than 25 percent in 2023–24.

How Economic Shocks Reversed Poverty Reduction Gains in Pakistan

The reversal did not happen overnight but through a series of shocks. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted labor markets and small businesses, robbing millions of income security. Global inflation, worsened by geopolitical crises such as the war in Ukraine, raised the cost of food and fuel far beyond the reach of low-income households.

Pakistan’s devastating floods in 2022 and later in 2025 further compounded misery, wiping out crops, displacing families, and erasing livelihoods across rural districts. Each shock revealed how fragile earlier gains truly were, especially for households living just above the poverty line.

Structural Barriers Limiting Pakistan’s Fight Against Poverty

Behind the shocks lie deeper weaknesses in Pakistan’s development model. Much of the workforce remains trapped in informal and low-paid jobs, while agricultural productivity stagnates. Public services such as education, health, and clean water remain unevenly distributed, leaving rural populations especially disadvantaged.

Without stable income sources or reliable safety nets, families are left vulnerable to sudden downturns. The World Bank notes that these systemic gaps made it nearly impossible for the poorest households to withstand recent crises.

Poverty in Pakistan is not evenly spread across the country. Rural areas continue to suffer far higher rates than urban centers, where opportunities for wage employment are more accessible. In provinces like Balochistan, the situation is particularly dire, with poverty levels exceeding 40 percent in several districts. Regional inequality has widened in recent years, as urban residents, though affected by inflation, still benefit from stronger networks, services, and infrastructure.

Government Initiatives and the Challenge of Poverty Alleviation

Pakistan’s government has responded by expanding social protection programmes such as the Benazir Income Support Programme, along with efforts to subsidize basic necessities. These interventions provide short-term relief, but the World Bank argues they remain insufficient in scope and effectiveness.

Limited fiscal space, weak governance, and frequent policy reversals undermine the impact of such programmes. Moreover, aid often arrives after crises hit, instead of preparing communities with stronger resilience beforehand. This reactive approach has kept millions vulnerable to falling back into poverty with every shock.

Pakistan faces a critical choice. Without meaningful reforms, poverty will continue to rise, deepening social and political instability. Sustainable reduction requires a mix of economic stability, job creation, and human capital investment. Strengthening education, healthcare, and rural infrastructure could build long-term resilience.

In Our Defence Podcast: Is Bangladesh Becoming East Pakistan 2.0?

In Our Defence Podcast: Is Bangladesh Becoming East Pakistan 2.0?  Himanta Taunts Gogoi “He Can Contest Elections in Pakistan”

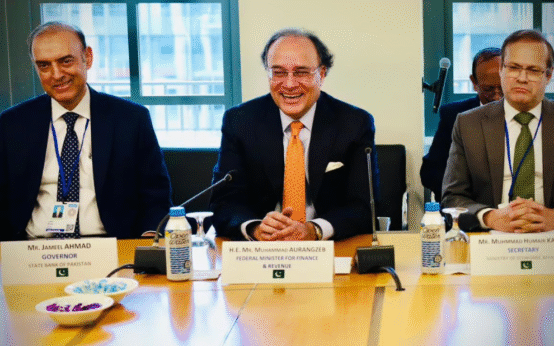

Himanta Taunts Gogoi “He Can Contest Elections in Pakistan”  Pakistan FM IMF Cannot Impose Conditions on National Interests

Pakistan FM IMF Cannot Impose Conditions on National Interests  PSX Market Surges IMF Nears Staff-Level Agreement

PSX Market Surges IMF Nears Staff-Level Agreement  Pakistan Among Early Adopters of Wi-Fi 7 in Asia-Pacific

Pakistan Among Early Adopters of Wi-Fi 7 in Asia-Pacific  Pakistan Poised to Launch 5G Services in Coming Months

Pakistan Poised to Launch 5G Services in Coming Months